Artburst Extras

The Four-Dimensional Kinetics of Gesture in Four Exhibitions at Mindy Solomon Gallery

Heather Rubinstein’s works, “In Search of Bel Esprit,” are inspired by Hemingway’s “A Moveable Feastm” and are currently on view at Mindy Solomon Gallery. (Photo by Zachary Balber, courtesy of Mindy Solomon Gallery)

At Mindy Solomon Gallery, in Miami’s ever-growing Allapattah Arts district, are four concurrent exhibitions by Victoria Martinez, Ali Smith and Andrew Casto, Heather Rubinstein, and Xavier Baxter. They cohere around a shared visual language of mark-making in abstraction borne through urgency, corporeality, and raw aggression. Together, they explore the four-dimensional kinetics of gesture as an expanded understanding of material gesture as spatial, temporal, corporeal, and phenomenological. Here are the third or fourth generation of successors to Abstract Expressionists and Action Painting. The work of ceramicist Andrew Casto could, perhaps, be described as “Action Sculpting.”

Mixed-media wall works as sculpture

New York-based artist finds her subject matter in the cities she inhabits. Martinez considers fabric, brick, and pigment as repositories of histories of migration, labor, and communal living. The artist’s exhibition title originates from a European cultural reference to Charles Baudelaire’s Flâneur, a French term used by this 19th-century French poet to describe an observer of modern urban life. Conceptually, her works are inspired by her urban walks, the act of moving through the city, serving as a form of ambulatory research. It involves observing a constantly changing urban palimpsest, one where inhabitants can cite seemingly endless information about each block, street corner, and avenue going back years, even decades, where facades are springboards for memory.

Victoria Martinez “Morningside Portals,” (2025) at Mindy Solomon Gallery. (Photo courtesy of the artist and Mindy Solomon Gallery)

Martinez is exhibiting mixed-media wall works as well as sculpture. The two-dimensional works moving across the wall read like intensely colored, yet petite, punctuations. The sculptures stand decidedly vertical and uncomplicated. Their common building materials contrast with the elegance of the installation. She stacks a single brick on each 6 x 6-inch wood post, which stand about 44 inches tall, some of which contain materials juxtaposing the permanence of concrete with soft, pliable fabrics, a yin-yang. These are shoved unceremoniously into the brick’s holes, inhabiting their inner space. They, too, are spare gem-like punctuations in the expanse of gallery white, lit by a wall of windows, and refer to the stuff of architecture.

The artist’s chosen language of art is deliberately rough and handcrafted, contrasting with the common options for illusionism in art. It aligns with the simplicity of Mexican iconography and vibrant colors, reflecting her cultural background. Her colors are typical of hot climates, easily evoking brightly painted buildings seen in tropical areas, and this transformative impulse to add color to the world is clearly visible in neighborhoods across the United States, including the artist’s Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago, her hometown.

Martinez condenses these into tactile surfaces designed to evoke her life experiences. The hot colors operate on a vibrational color spectrum rather than a greyscale. Purple contrasts with orange, while saturated matte paint is suppressed by shiny silver, to use the push/pull of color. She employs sheer gauze, a hand-stitched analog, which functions as color-modifying glazes.

Two Vantage Points

In the next room, the exhibition “Despite All,” Ali Smith and Andrew Casto explore gesture’s dimensional elasticity from two vantage points: the rapid improvisations of painting and the echo of gesture in ceramic sculptures. Each of the artists’ chosen materials, once pliable or even fluid, has now dried to remain in perpetuity, like capturing a fleeting thought.

Work by Ali Smith. (Photo courtesy of the artist and Mindy Solomon Gallery)

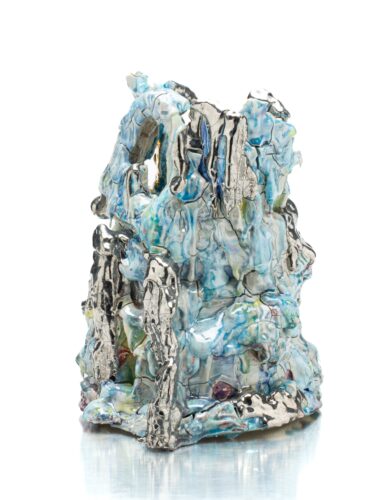

Casto’s ceramics reject the appearance of mastery commonly seen in the medium and give the illusion of disregard for detail. To look at them in the context of Meissen vases, they appear as temper tantrums in the ceramic studio, crafted with the refined materials porcelain and gold, which indicate intentionality. They are aggressive and playful and obstinate in their refusal to be “beautiful.” Rather, this term becomes expanded in his hands where gloopy and globby are not pejorative terms. The ceramics sometimes appear as if seen under a waterfall from the skillful modulation of the glazing.

Andrew Casto’s work at Mindy Solomon Gallery. (Photo by Zachary Balber, courtesy of Mindy Solomon Gallery)

It is through a mastery of materials that an artist can work with such freedom, to loosen the reins and let it take the lead. It is through active listening to the clay that the flow, the zone, is entered. This is where the “my kid could do that” response is simply off base and shortsighted.

Through his rejection of making functional objects, is an assertion that nothing more is needed. They are enough and do not need flowers, and the morality of being something useful, in the common sense of the word, is moot. The usefulness is not quantifiable, but the individual experience of art.

Smith’s paintings line the walls in counterpoint to the heaviness of Casto’s hand. Her mark-making is a facile calligraphy dancing, creating the rhythm and illusion of space through size and intensity of detail. One can sense the immediacy and the energy with which her hand moves. The imagery feels specific yet sometimes unintelligible, staying with abstraction, open to interpretation. A simple line drawing of a face feels like unresolved shorthand and contrasts fluency of her line. She, like Martinez, uses vibrational color. She is drawing as much as painting with the brush. They have a tempo, each swift mark like notes in a music score, establishing a rhythmic scaffolding for color. She describes her process as “living in the moment” of the brushstroke, treating abstraction as a space of risk and reinvention.

Within these works, one can see a commonality in the mark-making of Cecily Brown and the forms of second-generation Abstract Expressionist Norman Bluhm. The inclusion of cartoonist heads is a signpost to subject matter, yet it is not beneficial to the work’s overall gorgeousness.

The pairing of Smith’s kinetic mark-making and Casto’s physically dense objects demonstrates gesture’s ability to express both instant speed and the gradual process of accumulation, linking the quickness of human action with the slowness of geological processes. Smith’s “Teenage Daydream” is a bridge between the two artists.

Xavier Baxter, “Brave,” 2025. (Photo by Zachary Balber, courtesy of Mindy Solomon Gallery)

The third exhibition is Xavier Baxter’s “Resolute.” These are sculptural in their aggression and recall Abstract Expressionist Willem Dekooning. Like Dekooning, these paintings confront the figure, heavy with the history of figure painting, through violent mark-making: limbs and faces emerge and collapse within storms of pigment applied by brush, knife, scraper, and hand.

His surfaces are scarred, beaten, and examined. He seems to both add and subtract as part of his working process. He has a Phillip Guston-like compression of space and uncomfortable containment of the subject as if the frame were a space-limiting box. The heads of his figures are uncomfortably crooked to the side and approach the work of Basquiat.

Baxter aptly described his process as “wrestling with the figure.” His energetic gestures describe this exertion. His marks operate not as descriptive lines but as extensions of the body’s reach, torque, and impact. The scale of works like Look Forward (120” x 96”) amplifies this bodily dimension, and the paintings engulf the viewer, compelling a kinesthetic awareness of their own scale in relation to the artist’s movements. Gesture is both an imprint of muscular exertion and an invitation for collapsing the boundary between the artist’s labor and the viewer’s perception. Again, the viewer has the opportunity to step into this artist’s shoes and imagine the brush, loaded with paint, in their hand.

Inspired by Hemingway

The fourth exhibition, partly in a hall and partly in an office, is Heather Rubinstein’s “In Search of Bel Esprit.” Inspired by Hemingway’s “A Moveable Feast,” its title refers to early modernist Paris. In the novel, it’s a refuge for T.S. Eliot and a garden in central Paris. Hemingway’s chapter “Ezra Pound and His Bel Esprit” describes Pound’s efforts to raise money to free Eliot from a bank job. Literally meaning “fine mind” or “beautiful spirit” in French, bel esprit refers to a person of great wit or intellect.

Utilizing liquidity and gravity, Rubinstein’s paintings are made up of drips, washes, and fluid marks that highlight painting as an encounter between materials and gravity. Her vertical strokes, a gestural system, function rhythmically: dark, structural strokes establish percussive beats, while diluted washes and drips provide the counterpoint.

The artist’s gestures start at the top, as if “off screen.” This reflects Degas’ use of photography, framing an image as if seen through a window rather than the wider visual field, a historically significant development for artists in painting. Her gestures are subject to the pull of gravity. The overall coloration is tonal, except for Peonies. Here, the fuchsia dominates, serving as the subject matter and capturing the beauty of flowers in full bloom.

Heather Rubenstein painting at Mindy Solomon Gallery. (Photo by Zachary Balber, courtesy of Mindy Solomon Gallery)

These paintings are luscious and evoke bushes, foliage, the landscape of one’s yard. Like Casto, they refuse to be pinned down, remain in flux.

Taken together, these four exhibitions articulate a four-dimensional kinetics of gesture. They are spatial as gesture inscribes itself across the surface, asserting material flatness as it activates pictorial space. Each has a temporal aspect. The strokes are an archive of speed or slowness, rendering time palpable in its residue. They reference the corporeal: gesture indexes the body, recording reach, pressure, and exertion as visible traces. Through the phenomenological, gesture is completed in perception, allowing viewers to reperform its motion through visual tracking.

Martinez archives urban memory through stitched and painted surfaces. Smith and Casto oscillate between velocity and geological pressure. Baxter inscribes the body itself into the turbulence of the picture plane. Rubinstein deploys gravity to collapse paint into a cascade of experience.

Collectively, these artists reaffirm gesture’s ability to make the process visible: transforming marks into living records of action, movement, and time, much like the Abstract Expressionists. They originate from the action painters of the mid-20th century, such as Pollock, Franz Kline, and Willem De Kooning, and this approach was carried forward by Joan Mitchell and Helen Frankenthaler, who created nuances of space and the organic world into their paintings. The exhibitions emphasize the immediacy of the hand and the intelligence of untethered intuition, salient in today’s discourse about AI.

WHAT: Victoria Martinez: “Flâneur,” Ali Smith and Andrew Casto: “Despite All,” Xavier Baxter: “Resolute,” Heather Rubinstein: “In Search of Bel Esprit”

WHERE: Mindy Solomon Gallery, 848 N.W. 22nd St., Miami

WHEN: 11 a.m. through 5 p.m., Tuesday through Saturday, and by appointment. Through Saturday, Sept. 6.

COST: Free

INFORMATION: 786-953-6917 and www.mindysolomon.com

ArtburstMiami.com is a nonprofit media source for the arts featuring fresh and original stories by writers dedicated to theater, dance, visual arts, film, music and more. Don’t miss a story at www.artburstmiami.com.