Visual Art

At PAMM, the Jiménez Twins Reimagine Afro-Cuban Spirituality Through Art

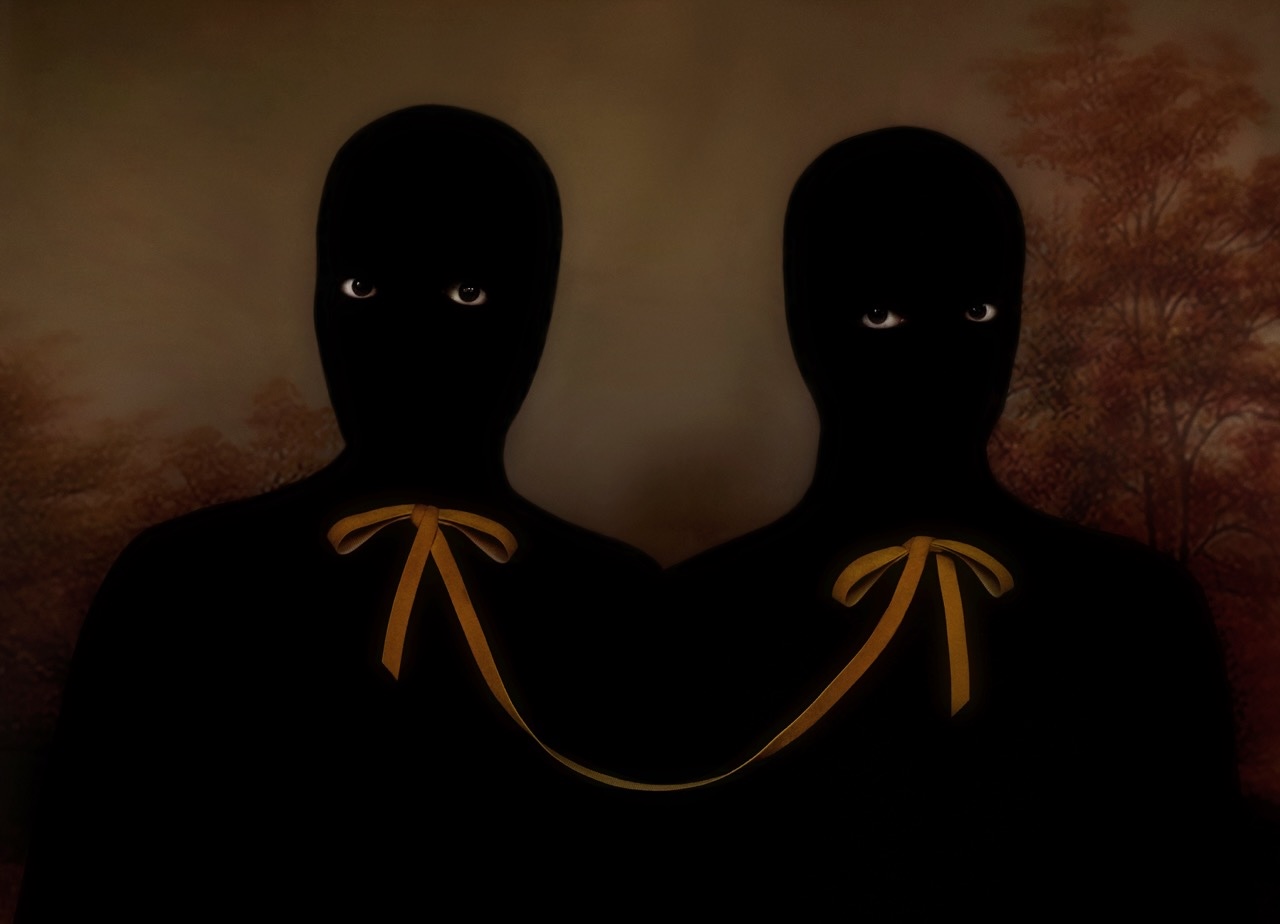

Cuban American photographers Elliot and Erick Jiménez debut their first solo museum exhibition with “El Monte,” opening August 28 at PAMM. Above, “El Monte (Ibejí),” 2024, archival pigment print on paper, 36 x 48 in. (Photo courtesy of the artists and Spinello Projects)

Cuban writer and ethnographer Lydia Cabrera published “El Monte” in 1954, a groundbreaking study of Afro-Cuban spirituality and oral traditions. Cabrera devoted her life to documenting the Lucumí faith—also known as Santería or Regla de Ocha—a syncretic religion that emerged in Cuba from Yoruba belief systems brought by enslaved Africans and merged with Catholicism. Her work preserved stories, rituals, and sacred knowledge that might otherwise have remained hidden, earning her the trust of communities that rarely shared such practices with outsiders. Cabrera died in exile in Miami in 1991, but her scholarship continues to shape the way Afro-Cuban culture is understood worldwide.

With the opening of the exhibition, Cabrera’s presence resonates in a new way. “El Monte,” the first solo museum exhibition by Cuban American twin photographers Elliot and Erick Jiménez, opens on Thursday, Aug. 28, at the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM).

The show draws inspiration from Cabrera’s seminal text, published in English for the first time in 2023 by Duke University Press.

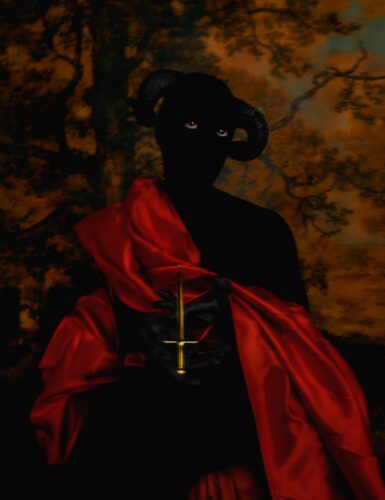

The Jiménez brothers use in-camera techniques, staging, and body paint to achieve a painterly effect. “Who is the Ram and Who is the Knife? ” (2025), archival pigment print on canvas with metal glitter, 64 ½ x 50 in. Courtesy the artists and Spinello Projects. (Photo courtesy of the artists and Spinello Projects)

PAMM’s Associate Curator Maritza Lacayo, who organized the exhibition for the museum, sees the translation as pivotal. “‘El Monte’ is one of the most influential books in Cuban cultural history, and now, with its English translation, it has become accessible to a new generation of readers,” she said. “For the Jiménez twins, who grew up in Miami as Cuban Americans, the translation is deeply meaningful. It connects them to their heritage in their first language.”

Elliot Jiménez echoes the sentiment. “We felt that having our first exhibition here in Miami, referencing Cabrera’s book, was important—especially because when we began working on the show, we learned the book was being translated into English for the first time. That widens access not just to a new audience, but also to first-generation Cuban Americans like us. Many of our peers don’t necessarily speak Spanish, so now they can finally read this work and connect to it.”

For the artists, Cabrera’s text is not a script to be illustrated but a catalyst. “We didn’t set out to necessarily recreate Lydia Cabrera’s book—we set out to create a world inspired by its spirit,” says Elliot. “‘El Monte’ is not an illustration; it’s a response born of heritage and imagination.”

Miami-born photographers Elliot and Erick Jiménez explore work that reflects on Afro-Cuban spirituality and cultural memory. Their first solo museum exhibition, “El Monte,” opens Thursday, Aug. 28 at PAMM. (Photo courtesy of the artists)

Erick Jiménez adds that Cabrera’s exile gives the exhibition particular resonance in Miami. “It’s an interesting circle—that Lydia was forced into exile and lived her last years here, and now her work comes alive again in this city,” he says. “Our own family also fled Cuba, seeking asylum in Costa Rica before coming to Miami. For us, and for so many in this community, that story of displacement and refuge feels deeply familiar.”

Visitors to the exhibition will encounter an immersive environment: a nocturnal forest where flora and spirits come alive. At its center stands a towering Ceiba tree, sacred in Afro-Cuban cosmology and believed to connect heaven, earth, and the underworld. Inside the tree, a space represents the shared womb of twins, housing the Ibejí Chapel, dedicated to the divine twins of Lucumí who symbolize duality, balance, and sacred siblinghood.

“Our idea was that you walk into ‘El Monte’ at night,” according to Erick. “The space is designed intentionally so that visitors don’t just look at works on a wall, but wander through a forest, encountering figures along the way. Inside the Ceiba, the space shifts—it becomes a chapel, more tied to Catholic references. That duality is at the heart of the show, reflecting both the history of the island and our own story as twins, bilingual Cuban Americans of mixed heritage.”

For the brothers, the Ibejí imagery is deeply personal. “We see the Ibejí not just as divine twins in Lucumí, but as a reflection of ourselves,” says Elliot. “Their story—of loss, of care, of sacred bond—becomes a way to tell our own.”

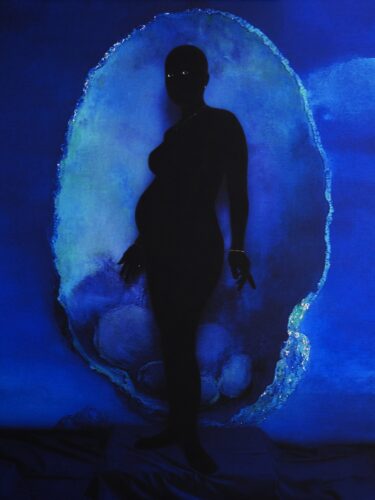

The exhibition also reflects on motherhood, presence and absence, and the dualities that have shaped the artists’ lives. These personal narratives are interwoven with references to Western art history, Catholic iconography, and Yoruba mythology, creating what they call a “visual syncretism” that invites connections across cultures.

“Children of the Moon,” (2025), reflects the twins’ interest in myth, duality, and diaspora. Archival pigment print on canvas with raw brass and metal glitter, 55 x 40 in. (Photo courtesy of the artists and Spinello Projects)

Known for their painterly approach to photography, the brothers reject digital manipulation in favor of experimental techniques. “All of our works are photographs. There’s no Photoshop—everything happens on set,” explains Elliot. “We build the costumes, the sets, the lighting, and even print on canvas, working the surface while the ink is still wet to give it a painterly effect. We want to push photography beyond documentation, to expand what it can be inside a museum.”

Among their recurring motifs are shadow figures—anonymous bodies with only the eyes visible.

Elliot recalls that the religions the brothers that surrounded them growing up —Lucumí, Santería, Palo—were always practiced in hiding.

“So we use concealment to reference that secrecy. At the same time, the anonymity lets viewers see themselves in the work. Even if they don’t know Santería, they can connect to themes of resilience, concealment, and transformation.”

Exhibition organizer Lacayo explained that this strategy enriches the show. “They’re creating a space that reflects how spirituality exists—in fragments, in mystery, in what’s seen and what’s hidden. That ambiguity is part of the story.”

For the Jiménez brothers, Miami is not just a backdrop but an essential part of the narrative. “If you had told me five years ago that our first solo museum show would be in Miami, I probably wouldn’t have believed it,” says Elliot.

He explains that the twins moved to New York a decade ago because they felt photography didn’t have much visibility in Miami.

“Things have changed, and coming back with this exhibition feels surreal—a full circle moment.”

Erick added: “It feels different to show this work here rather than anywhere else. Miami is where we were born, and it’s also where Lucumí and other Afro-Cuban traditions are so present in daily life. That means audiences here can connect to it in a way that’s very personal. For us, that makes it the most special of all.”

In works like “The Rebirth of Venus,” (2025), the artists merge photography with embellishments such as crystals and pearls, creating images that blur the line between sacred ritual and Western art history. (Photo courtesy of the artists and Spinello Projects)

Lacayo underlined the significance of the museum’s role. “Whenever we do an artist’s first solo museum show, we’re investing in that artist,” she said. “Because they were born here, and because their story mirrors so many others in Miami—first-generation Americans living between cultures—it felt essential to debut this exhibition at PAMM. It couldn’t have been anywhere else.”

Ultimately, “El Monte” is a dialogue across generations—between Cabrera’s anthropological work and the Jiménez brothers’ artistic practice. That dialogue is not only conceptual but literal: the exhibition incorporates field recordings Cabrera made during her investigations in Cuba.

“Through those recordings, Cabrera is not just referenced, she’s there,” says Lacayo. “Her voice and the chants she documented become part of the soundscape.” Cabrera gained extraordinary access at a time when women were rarely allowed into such sacred spaces. By recording babalawos—male priests whose rituals were traditionally closed to outsiders—she preserved songs, chants, and oral histories that might otherwise have been lost.

In the PAMM galleries, those recordings mingle with the Jiménez brothers’ imagery, bridging past and present. She returns to the city where she lived her final years not only as an intellectual presence but as a living voice.

The brothers believe that Lucumí has existed for centuries in hiding, and their exhibition is to make the “invisible visible” while honoring a tradition passed down orally and shaping it into something new.

And in that space of images and sound, Cabrera’s voice does not echo from the past but breathes into the present, keeping Afro-Cuban memory alive in Miami, the city she once called home.

WHAT: “Elliot and Erick Jiménez: El Monte”

WHERE: Perez Art Museum Miami (PAMM), 1103 Biscayne Blvd., Miami

WHEN: 11 a.m. to 6 p.m., Monday, Friday, Saturday and Sunday, 11 a.m. to 9 p.m., Thursday. Closed Tuesday and Wednesday. Opens Thursday, Aug. 28, 2025 through Sunday, March 22, 2026

INFORMATION: (305) 375-3000 or www.pamm.org/en/visit

ArtburstMiami.com is a nonprofit media source for the arts featuring fresh and original stories by writers dedicated to theater, dance, visual arts, film, music, and more. Don’t miss a story at www.artburstmiami.com.